This personal essay was an invited article for The Doctor Blog by ZocDoc.

July 31, 2015

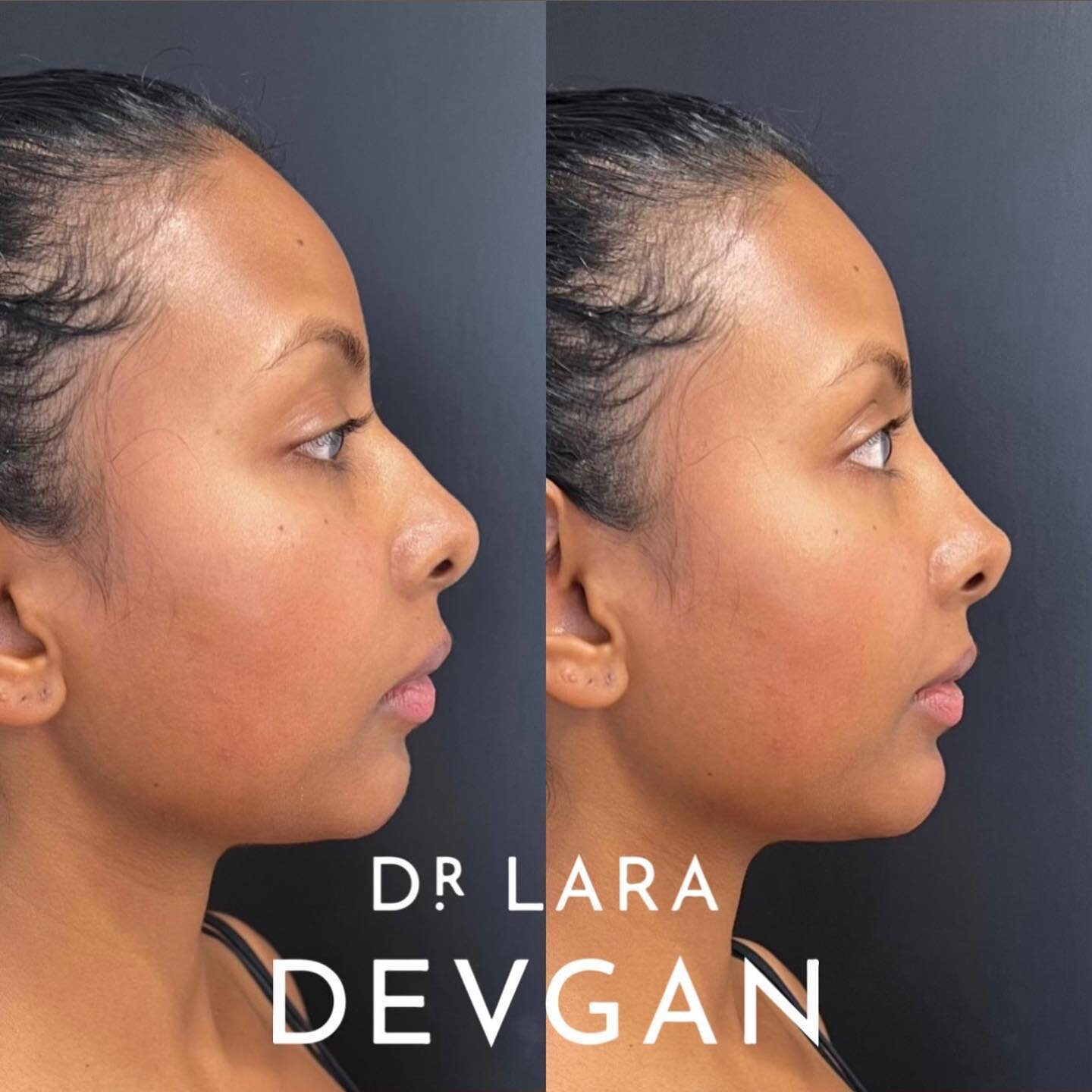

By Lara Devgan, MD

I have given a number of medical talks over the years-– reports on my research, reviews of surgical topics, mentoring speeches, and grand rounds, among others. I prepare for these talks extensively but tend to speak extemporaneously to engage better with my audience. I’m pleased to say that, in general, I have received good feedback. Several times, however, I have been given the “constructive criticism” that my voice is “girly” or “immature.”

I will be the first to admit that I am not an expert on oration or public speaking. I have no background in stage acting or performance. And despite the speech accolades of my youth (as a high schooler I was the Lincoln-Douglas Debate state champion in California, and while in college a friend and I won the Adams Cup for Parliamentary Debate at Yale), I know very little about what the ideal speaking voice is supposed to sound like.

My focus for my medical talks is simple and content-based: speak clearly, convey my message, and use a voice that my audience will understand. To be sure: I am a woman of petite stature, and my speaking pitch is soprano to mezzo-soprano. I am also a fully grown adult with gray hair and a busy plastic surgery practice, who has published and spoken extensively in my field.

Yet with recent media attention to the many perceived flaws with female voices, I cannot help but wonder about the extent to which this phenomenon applies to the world of science and medicine.

Women have been criticized for “upspeak”-– using a voice that trails upward in pitch at the end of a sentence. This is a version of a “Valley Girl” lilt, and it has been described by linguist Mark Liberman as a speech pattern that makes it sound like we are asking for permission or posing a question. It sounds weak and lacks authority, we are told. Kelly Ripa is an example of a woman who frequently employs upspeak.

Conversely, women are also criticized for “vocal fry”-– using a hoarse, low-pitched rumble that is commonly employed to add emphasis, depth, or satire to speech. According to NPR On the Media host Bob Garfield, this sounds unrefined and lacks gravitas; he says it is “annoying,” “repulsive,” and “mindless.” Examples of vocal fry users include Tina Fey and Lindsay Lohan.

Interestingly, vocal fry has been described as “the opposite of upspeak” by The Daily Dot’s Amanda Marcotte. She argues that it conveys more authority than monotone speech because the voice takes on a lower pitch at the end of a sentence. Yet it is still derided as an irritating female speech affectation.

There is also a more general series of complaints about women’s voices that reverberates in the media. Hillary Clinton’s voice is too “nagging” according to Fox News journalist Mark Rudov, Sarah Palin’s voice “causes ears to bleed” according to the Free Wood Post, and Ann Coulter’s “whiny voice is so distracting” according to AOL TV reporter Jane Boursaw. Politics aside, these complaints cross the aisle to suggest that there are very few pleasing and acceptable ways women can speak.

Taken as a whole, criticisms of female voices of authority are difficult to make sense of. If women’s voices are derided for being high-pitched, low-pitched, varied, and, well, feminine, how exactly are women in professional roles supposed to speak?

In medicine, public remarks are intended to educate and elucidate content-heavy material. Perhaps even more so than in other realms, the topics we discuss publicly are technical and complex: molecular biology, anatomy, pharmacology, physiology, pathology, and more. While speaking voices should certainly be clear, the societal trend of policing women’s voices distracts and detracts from this important subject matter.

There is no way to take the woman out of her own voice, nor should there be. Women have smaller vocal folds and laryngeal cavities than do men, generally speaking, and it is unsurprising that the higher pitch and lower volume of female speech patterns reflects this. Also unsurprising is the female tendency to use forms of vocal inflection to vary oratory sounds, given that there is less possible volume variation.

This variance in women’s speech does not make it girly, immature, whiny, cloying, annoying, or otherwise objectionable. It simply makes it the way half of the population tends to vocally project. And in medicine, as in all fields, it makes it worth listening to.